Myth: Universal Healthcare in America Would be Very Expensive

Healthcare is like education: everybody needs it, regardless of their budget, but it’s expensive. That’s why all advanced economies, except the United States, fund it through taxation.

Debunking Myths About Universal Healthcare in America

Right now, in the United States, individuals and employers pay insurance premiums; people pay cash co-payments for drugs; and state governments pay a share of Medicaid costs. An often proposed alternative to the contemporary multi-payer system is single-payer, also referred to as Medicare for All. Key elements of single-payer include unified government financing, universal coverage with a single comprehensive benefit package, elimination of private insurers, and universal negotiation of provider reimbursement and drug prices. Two-thirds of Americans support providing universal health coverage through a national plan like Medicare for All.

An example of how we currently pay for healthcare would be say, a secretary earning $50,000 a year, who has employer-sponsored health insurance at a total cost of $15,000. In reality her labor compensation is $65,000 (that’s what her employer pays in exchange of her work), but the secretary only gets $50,000. The executive earning $1,000,000 also pays the same $15,000 for his healthcare. This is a terrible funding mechanism.

Our Dysfunctional Healthcare System:

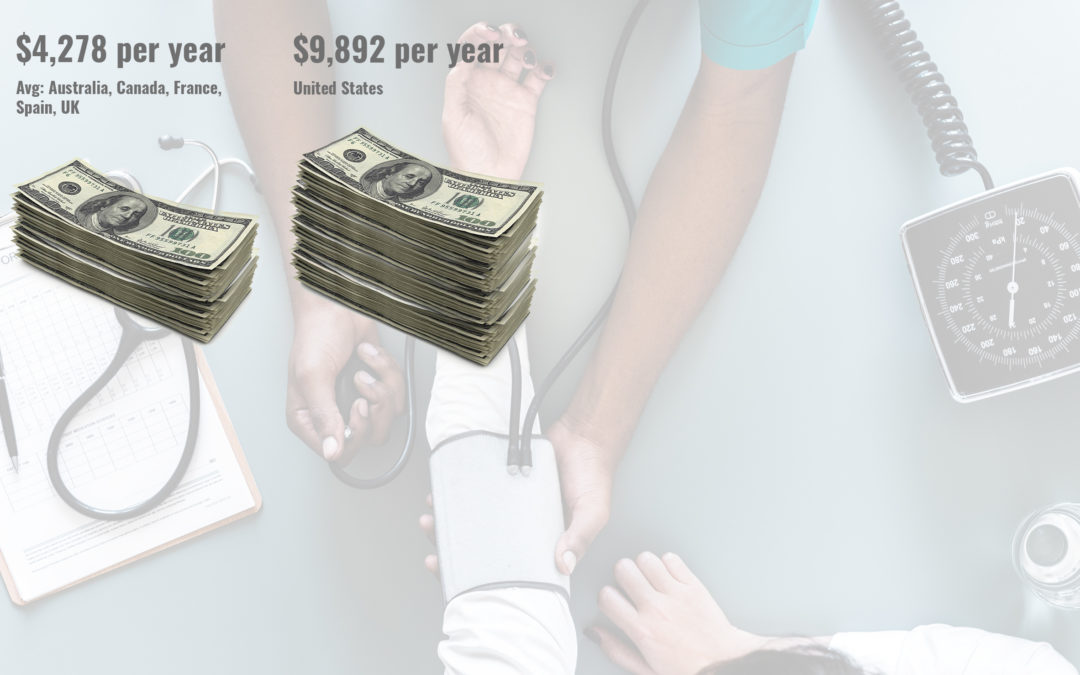

We pay more than twice as much per person on total health care spending and on prescription drugs in comparison to other developed countries. This spending totals nearly 18 percent of our economy.

Between 2008 and 2018, premiums for employer-sponsored insurance plans increased 55 percent, twice as fast as workers’ earnings (26 percent). Over the same time period, the average health insurance deductible for covered workers increased by 212 percent.

An average employer-sponsored family health insurance policy now exceeds $28,000 per year, with employers paying about $16,000 and employees paying about $12,000.

Almost half (45 percent) of US adults ages 19 to 64, or more than 88 million people, were inadequately insured over the past year (either they were uninsured, had a gap in coverage, or were underinsured; that is, they had insurance all year but their out-of-pocket costs were so high that they frequently did not receive the care they needed).

In 2019, 67.8 million workers across the country separated from their job at some point during the year—either through layoffs, terminations, or switching jobs. This labor turnover data leaves little doubt that people with employer-sponsored insurance are losing their insurance constantly, as are their spouses and children.

Compared to other developed countries, the US ranks near the bottom on a variety of health indicators including infant mortality, life expectancy, and preventable mortality.

Cost Saving Potential under Medicare for All

According to research conducted by the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) Medicare for All has the potential to achieve major cost savings in its operations relative to the existing U.S. health care system. They estimate that, through implementation of Medicare for All, overall U.S. health care costs could fall by about 19 percent relative to the existing sys¬tem.

The most significant sources of cost saving will be in the areas of:

- administration (9.0 percent savings in total system costs)

- pharmaceutical pricing (5.9 percent savings in system costs)

- establishing uniform Medicare rates for hospitals, physicians, and clinics (2.8 percent savings in system costs)

In our current system, doctors, hospitals and other health care providers are paid by a number of insurers, and those insurers all pay them slightly different prices. In general, private insurance pays medical providers more than Medicare does. Under a Medicare for all system, Medicare would pick up all the bills.

Patients in the United States pay the highest prices in the world for prescription drugs. That’s partly a result of a fractured system in which different payers negotiate separately for drug benefits. A Medicare for all system would have more leverage with the drug industry because it could bargain for the whole country’s drug supply at once.

The complexity of the current American system means that administrative costs are very high. Insurance companies spend on negotiations, claims review, marketing and sometimes shareholder returns. One key advantage of a Medicare for all system would be to strip away some of those overhead costs.

How Would Americans Pay for Medicare for All?

The main difference between the insurance premiums currently paid by American workers and the taxes paid by workers in other countries is that their taxes are based on ability to pay. The income tax has a rate that rises with income. Payroll taxes are proportional to income, at least up to a limit. Insurance premiums, by contrast, are not based on ability to pay. They are a fixed amount per covered worker and only depend on age and the number of family members covered. Insurance premiums are the most regressive possible type of tax: a poll tax. The secretary pays the same amount as the executive.

The United States currently spends close to 20% of its national income on health. Elderly Americans and low-income families are covered by public insurance programs (Medicare and Medicaid, respectively), funded by tax dollars (payroll taxes and general government revenue). The rest of the population must obtain coverage by a private company, which they typically get via their employers. Insurance, in that case, is funded by non-tax payments: health insurance premiums.

Although they are not officially called taxes, insurance premiums paid by employers are just like taxes – but taxes paid to private insurers instead of paid to the government. Like payroll taxes, they reduce your wage. Like taxes, they are mandatory, or quasi-mandatory. Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, it has become compulsory to be insured, and employers with more than 50 full-time workers are required to enroll their workers in a health insurance plan.

Many people believe that the United States has a progressive tax system: you pay more as you earn more. In fact, if you allocate the total official tax take of the United States across the population, the US tax system looks like a giant flat tax that becomes regressive at the very top. And if you add mandatory private health insurance premiums to the official tax take, the US tax system turns out to be highly regressive. Once private health insurance is factored in, the average tax rate rises from a bit less than 30% at the bottom of the income distribution to reach close to 40% for the middle class, before collapsing to 23% for billionaires.

The health insurance poll tax hammers the working class and the middle class. At the bottom of the distribution, it’s not as onerous as sales and payroll taxes. But that’s because many low-income Americans rely on a family member to cover them, enroll into Medicaid, or go uninsured. For the middle-class, the burden is enormous. Take a secretary earning $50,000 a year, who has employer-sponsored health insurance at a total cost of $15,000. In reality her labor compensation is $65,000 (that’s what her employer pays in exchange of her work), but the secretary only gets $50,000. The executive earning $1,000,000 also pays the same $15,000 for his healthcare. This is a terrible funding mechanism.

The most fundamental goals of Medicare for All are to significantly improve health care outcomes for everyone living in the United States while also establishing effective cost controls throughout the health care system. These two purposes are both achievable. As of 2017, the U.S. was spending about $3.24 trillion on personal health care—about 17 percent of total U.S. GDP. Meanwhile, 9 percent of U.S. residents have no insurance and 26 percent are underinsured—they are unable to access needed care because of prohibitively high costs. Other high-income countries spend an average of about 40 percent less per person and produce better health outcomes. Medicare for All could reduce total health care spending in the U.S. by nearly 10 percent, to $2.93 trillion, while creating stable access to good care for all U.S. residents.

Proposals such as Medicare for All would replace the current privatized poll tax by taxes based on ability to pay. Some believe that it would result in a big tax increase for America’s middle class. But the data show that it would, in fact, lead to large income gains for the vast majority of workers.

Take again the case of a secretary earning $50,000 in wage and currently contributing $15,000 through her employer to an insurance company. With universal health insurance, her wage would rise to $65,000 – her full labor compensation. With an income tax of 6% – which, if applied to a base large enough, would be enough to fund universal health insurance – she would have to pay about $4,000 more in tax. But the net gain would be enormous: $11,000. Instead of taking home $50,000, the secretary would take home $61,000.

Conclusion

Supporters of Medicare for All are right. Funding universal health insurance through taxes would lead to a large tax cut for the vast majority of workers. It would abolish the huge poll tax they currently shoulder, and the data show that for most workers, it would lead to the biggest take-home pay raise in a generation.

MYTH BUSTED!

Medical Care and the Health Risks Forced Upon Women by Abortion Bans

Between a Rock and a Hard Place Much of the political debate about abortion in America focuses on abortions performed late in pregnancy, but the overwhelming majority of them occur in the first trimester. Forty-three percent of all abortions occur in the first six...

The more steps you and your family can take to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the safer you and your loved ones will be.

Mask Up! Many People With COVID-19 Do Not Know They Have It!Your Loved One Could Become Seriously Sick or Die from COVID-19Julianna TruesdaleWhy is it important to wear a mask around my relatives? COVID-19 cases and deaths are rising across...

Do you know why United States Healthcare costs are so high?

Do you know why United States Healthcare costs are so high? Julianna Truesdale Americans have reached a new high in support for having presidential elections based on the popular vote instead of the Electoral College. While most Americans –...

Americans Pay Almost Double for Health Care

The United States has the most expensive health-care system in the world, but when comparing our population health with our international peers we have poor health outcomes.